It’s been nearly thirty years since Tony Todd first appeared as Candyman in an underground parking garage, seductively urging graduate student Helen Lyle (Virginia Madsen) to “be my victim.”

The 1992 film went on to become a classic, as well as a text that opened up discussions about racial politics and the responsibility of the creators who are representing marginalized communities from which they do not self-identify. (For more, listen to my Horror Queers episode on the original film)

These factors are worth acknowledging as the new Candyman arrives in theatres. Shepherded by executive producer Jordan Peele and directed by Nia DaCosta (who co-writes, along with Peele and Win Rosenfield), the new film acts as both a direct sequel to the original film, as well as a gentle reclamation of the myth of the titular character and the community from which he hails.

Candyman ‘21 ignores the two previous (inferior) sequels from the 90s and, after a 1977-set prologue, picks up the action in present day Chicago. The notorious Cabrini Green housing projects have been mostly demolished to make way for gentrified condos, though a few of the derelict properties remain standing in a fenced-in area. The prologue sets the stage as a young boy (Rodney L Jones III) witnesses an act of (white) police violence against a Black man with a hook for a hand. This scene and the players will be re-contextualized several times over the course of the film, but the murder of Sherman Fields (Michael Hargrove) is an event with significant historical ramifications within the community.

In the present, Anthony McCoy (Yahya Abdul-Mateen II) is an aspiring artist dating gallery employee Brianna Cartwright (Teyonah Parris). They’ve recently moved into one of the aforementioned gentrified condos, which affords Brianna’s gay brother Troy (Nathan Stewart-Jarrett) – and by extension the film – an opportunity to introduce the urban legend of Helen and Candyman. Later, when Anthony receives middling feedback from Brianna’s boss, art dealer Clive Privler (Brian King), he turns to Candyman for inspiration. This brings him into contact with laundromat owner William Burke (Colman Domingo) who fleshes out the myth, including Sherman’s fate from 1977. Shortly thereafter, Anthony is stung by a bee and begins to change – physically and mentally – as he succumbs to his new obsession.

In this way Candyman operates on two complementary and intertwined narratives: the film is part possession story as Anthony’s wound festers and corrupts him. The other part involves a broader discussion about the intersection between racialized violence, black trauma, and art. Taking its cues from the origins of Candyman, nee Daniel Robitaille, who was a painter, Candyman interrogates the way that art becomes commodified and “more valuable” by broader (read: white and wealthy) audiences if it is associated with Black trauma and tragedy.

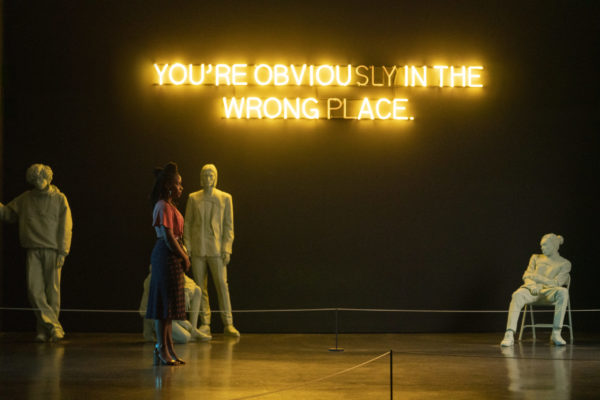

This ties directly into the discussions about land and privilege from Rose’s original film, which ties into Anthony and Brianna’s new house, as well as the location of the art gallery. The film is unafraid of wading into discourses about who profits from gentrification, which is literally the source of character conflict when Anthony butts heads with uppity white art critic Finley Stephens (Rebecca Spence).

For some, this will undoubtedly spark accusations of politicized entertainment. And in this instance, those idiots will be 100% correct: there’s a barely concealed rage in DaCosta, Rosenfield and Peele’s screenplay that is undeniably a response to the racist history of America. The film doesn’t name drop the events of the last year (in part because it was intended for release in 2020 before being delayed by the pandemic), but it also doesn’t need to, because none of this is new.

Candyman very openly acknowledges the historical legacy of racism and how it infects, poisons and destroys Black lives. One of the film’s most beautifully rendered recurring visual motifs is puppetry animation by Manual Cinema, which depicts multiple instances of trauma while sidestepping triggering real life violence. The sequence that accompanies the closing credits, in particular, is incredibly evocative; it’s upsetting and cathartic in equal measures and proves to be the perfect way to summarize the film’s themes.

So political ambitions aside, how does the film fare as a piece of entertainment?

The good news is that with the exception of one minor hiccup, it’s excellent (a development late in the film needed just a few extra scenes of set-up to work effectively). Candyman is incredibly well shot by DaCosta and cinematographer John Guleserian, who use recurring upside down tracking shots of the Chicago skyline, as well as copious amounts of mirrors, to create an unsettling mood and maintain the omnipresent threat of the Candyman spectre.

Speaking of mirrors, DaCosta makes great work of reflections as a source of doubling (to mark Anthony’s own consumption by Candyman), as well as an outlet for fear. The film wisely understands the power of withholding Candyman’s rampages and the staging of the kill scenes, in particular, is incredibly memorable. Candyman is only glimpsed in reflection and the staging of each death scene is different, which guarantees they are each memorable and unique (my favourite involves a long, slow drone shot pulling back from a window. It’s stunning).

Candyman has never been more of a shadowy figure than he is here; seeing so little of him, despite lording over everything (again, just like the original film) grants both the character and the myth so much power. The effect is so impactful that at one point when a character begins to chant Candyman’s name, I fully gasped aloud “No!”

Adding to the film’s strengths is a truly disgusting display of practical effects as Anthony’s obsession quite literally eats away at him. Throw in engaging performances by Abdul-Mateen II and Parris, who share the protagonist role, and reverent, but not overbearing, callbacks to the first film, and Candyman is an unabashed success.

Candyman is gorgeous, emotional, scary, and, most importantly, it will prompt vital discourse that simply cannot be ignored. Nia DaCosta has crafted one of the year’s best horror films and while audiences may be hesitant to say the titular character’s name, they’ll have no difficulty remembering hers after this gem. 4.5/5

Candyman is in theatres Aug 27, 2021

Lmao this reviewer wants so badly to be woke. Can’t stand him on BD. Can’t stand him here. Another run-of-the-mill snowflake.

Boy, it’s a damned good thing you came here to this site to read a review by someone you can’t stand. Thank you for looking out for all us fools who might draw our own opinions about the film, the review, or the reviewer. I’m thrilled I don’t have to think at all. You’ve definitely a-woke-n me.